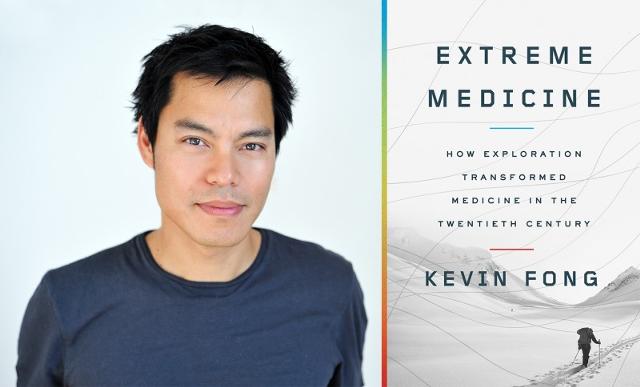

I felt pretty smart figuring out how to call today's interviewee over in London using a tape recording call proxy and an AT&T calling card. Meanwhile, he's literally a rocket scientist. Well, not technically, but does hold degrees in medicine, astrophysics and engineering, and is an honorary senior lecturer in physiology at University College London, where he is is Anaesthetic Lead for both the Patient Emergency Reponse Team and Major Incident Planning. He's also completed specialist training in anaesthesia and intensive care medicine, has worked with NASA's Human Adaptation and Countermeasures Office at Johnson Space Center in Houston and the Medical Operations Group at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral. He currently works as a consultant anaesthetist at University College London Hospital, where he's also the founder and associate director of the Centre for Altitude, Space and Extreme environment medicine. In addition to appearing in a number of space-related TV programs in the UK, he's most recently is the author of the book Extreme Medicine: How Exploration Transformed Medicine. He also knows how to operate a Twitter account!

I felt pretty smart figuring out how to call today's interviewee over in London using a tape recording call proxy and an AT&T calling card. Meanwhile, he's literally a rocket scientist. Well, not technically, but does hold degrees in medicine, astrophysics and engineering, and is an honorary senior lecturer in physiology at University College London, where he is is Anaesthetic Lead for both the Patient Emergency Reponse Team and Major Incident Planning. He's also completed specialist training in anaesthesia and intensive care medicine, has worked with NASA's Human Adaptation and Countermeasures Office at Johnson Space Center in Houston and the Medical Operations Group at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral. He currently works as a consultant anaesthetist at University College London Hospital, where he's also the founder and associate director of the Centre for Altitude, Space and Extreme environment medicine. In addition to appearing in a number of space-related TV programs in the UK, he's most recently is the author of the book Extreme Medicine: How Exploration Transformed Medicine. He also knows how to operate a Twitter account!

When astronauts go into space, how quickly do the zero-g related ailments start to set in?

The effects of space flight on the human body start as soon as you deploy. As soon as the main engine cuts off and you are weightless, you body starts responding to that environment. All of the effects begin. Your bones begin to waste, your muscles begin to waste, but you don't notice it at first, it's gradual. Things you'll notice in the first 24-48 hours are nausea, possibly vomiting. A reasonable number of rookie astronauts will get either or both of those. And disorientation--this is because of the effects of the loss of weightlessness, the accelerometry mechanisms in what we call the otolith organs--they are responsible for sensing linear acceleration and when you're in space they don't sense it really well. That's the first thing you'll notice, but all of this is happening from the moment you're in orbit. Â

How long-term are the negative effects? How long after returning to earth will you suffer?

So for crews coming back from a typical 10 to 16 day mission, they would be back to normal within a couple of days, or at least feel pretty normal--they get their earth legs back in a couple of days. The guys who take a little bit longer to get back to normal are the long-duration crew members. Those people have been up for months and months. They used to have a rule of thumb that it takes a day for every week being in space to feel normal again. That's not quite right, but that's basically to say that for the long duration it did take a little while longer. When you come back, the worst of the effects you feel in the first few hours, and the 24-48 hours. They used to let the crews jump in a car and drive themselves home, but they stopped doing that now because there were one or two incidents where people were disoriented driving down the highway. It's a little bit like getting off a ship after a long ocean voyage. You'd acclimatized to a new environment and your brain has to get used to a very different situation.

Are there any positive benefits of being weightless for a while?

You need to think of space as though it's an extreme environment, like climbing a mountain, or walking to the South Pole, or walking in the desert in an expedition. That's the best way we can conceptualize it. Just because they've got heat and lights up there, and they're floating around--and it is fun, weightlessness, they all say they love floating around. That doesn't make it any less of a challenge on the human body. What we know of space is what we know of all extreme environments, which is that we can go there, we can exist there, we can persist there, but it's not forever and it's not without penalty. So no, I don't think are any real health benefits of going into space--unless of course you count that they travel sufficiently fast enough to be a couple fractions of a second younger than their contemporaries on earth. Â

When you were in school, what other areas of medicine did you consider pursuing besides anesthesiology, or did you always know you wanted to go with that?

No, I went into medicine because I wanted to be a doctor, what felt like a true vocation. You've really got to want to do it. I was studying astrophysics at the time, knew I wanted to do something practical and was generally a benefit to people. I thought I'd be a family practitioner or something--I was going in a bit later than the other students because I'd already done a degree. I thought I was going to have a quiet family practitioner life somewhere in the west country.

As I studied medicine, I did miss that whole approach of physics, which is very reductionist--you could resolve anything with some fundamental principles. That's not always present in medicine in a very frustrating way. Â When I studied physics, you could sit there in front of your lecturer and go, "Why does the sun shine?" "The sun shines because it's hot and the heat is manifest in a number of wavelengths, some of which are visible, and that's why it shines." "Well then why is it hot?" And he'd say, "There are nuclear reactions going on in the core because of fusion, etc." You could go on and on like that, to an axiomatic extent. Whereas in medicine you might say, well, why do we give this drug? Â "We give this drug because more people live longer if they take it than if they don't." And you say, well, why is that the case? And the answer was very often, "Well, we don't really know--we know people do better on this drug because the trials say so and we're unsure of the precise reason why that happens." I didn't like that very much, so I wanted to go in an area where you had the most reductive approach to the problem as possible. So that led to anesthesiology. Most people don't really think much of anesthesiology as a specialty--a lot of people don't even realize it's a medical specialty in its own right--at least in the UK they tend not to. But in fact anesthesiology is a lovely subject in which you look at whole body integrated physiology, you try and work out how it's working, how it's perturbed by disease, and you're there in real time trying to work out what the effects of the drugs you're giving are, on that physiology, and what the effects of any diseases present superimposed on that might be. All that appealed to the physicist in me really. Â

When in your career did you pick up your writing skills?

I studied medicine as what we call a "mature student," after I'd done a first degree, so I was paying to way through my second degree. I worked for a student newspaper when I was in university, and I also tried to pay my way by writing the occasional article here and there for magazines. I worked out that you can find a medical angle to pretty much any story you want--it was a good way to write about stuff. I did a little bit of very amateurish freelance journalism in and around the time when I was in med school, but not much. I used to kind of write for fun. But I never really considered myself a writer at that time. And then more recently, going back about seven or eight years, there was a higher education magazine that asked me to write a column for them. So, because I'd done all this stuff--done a bit of interning at NASA and stuff--someone asked me to write a diary when I was a junior doctor and I was doing this weird thing of running between being a junior doctor and hanging out at NASA and stuff. There were nine scientists and I was one of those scientists, so I wrote this diary, and the higher education magazine asked me to write a column for them.

Do you still practice medicine on a regular basis?

Oh yeah. I currently have just started with one of the air ambulances that's here in the UK. We are a trauma service that flies out of the County of Kent here in England. And that's really busy, because we get up very early. I leave home at a quarter to five in the morning, then we work a shift from seven to seven in the evening. So I'm doing that at the moment, which is great fun because we get to fly in helicopters, go to the scenes of these incidents and do as much as we can.

At what points in your career have you been the most scared?

I think fear for any clinician with any insight is a regular feature of your career. For us working in almost any part of medicine, if you know what you're doing and you understand the consequences of the decisions you're making, I think fear must be a regular feature of people's careers. Yesterday, I was flying the air ambulance, we landed the middle of somewhere, we were looking after people who were very, very sick, and you're pretty exposed out there. I would never tell you that I'm not scared in those moments. I think the worst of it though for me must have been going to the [1999] bombings of Soho. I was less than a year qualified when I went out to those bombings. I think I was probably pretty terrified. They are probably the worst injured people I have seen. I was very, very junior at the time. And again I was out of the hospital, very exposed--not quite on your own, but you don't have that normal comfort blanket of the rest of the hospital staff around you to watch your back. You're there with a very small team.

In the twenty seconds you're weightless in the Vomit Comet, does that feel like a long or short time? What are you able to do in 20 seconds?

The strangest thing is it feels like neither. Weightlessness is something we've all experienced--if you go for a jump shot in basketball, you're kind of weightless from the point where you've launched to the point you hit the ground again. Anything that's thrown in the air is effectively weightless. That feeling you get when you go over a hump-backed bridge, the butterflies in your stomach--it's like that but it goes on for much longer. So in that sense it feels like a very long time. It's fractions of a second when you do it normally. So you don't expect it to be dragged out over many seconds at a time. But, it is only 20-25 seconds. It's great fun. You don't want it to be over. It is a 30 second shot and you're upset when it's over. You want to keep flying.

What can you do besides go "Whee!" and enjoy it?

The Vomit Comet was never invented to be an amusement ride. A lot of people are doing good science on it, or testing of equipment, or improving procedures. There's a bunch of stuff you can do, everything from testing what medical procedures or equipment will work up there--that's on my side of things. I've been fortunate to be involved on flights where I wasn't shaking down a piece of equipment, or doing any research. You do get the option to enjoy it. It's very hard to describe if you haven't done it. Genuinely, if you've ever had a dream about flying, for 20 seconds at a time, it's real. You can literally fly down the length of this vehicle if you get the right hand hold. It's a wonderful experience, despite all the stomach churning associations.

Based on everything you've researched and observed, how would you you'd least like to die?

A comedian used to say "'Gosh, that's a terrible way to die,' but I can't really think of a good way--they're all best avoided." But, in the things that I've done, the helicopter escape stuff made me think drowning would be pretty miserable. I'd have to choose that only because you get a sense of the panic, just in the immediate moments of immersion, the idea that might carry on and be unable to get to the surface, fighting the uncontrollable urge to breathe. Knowing what that would do but not being able to fight it off forever, I think that would be pretty horrible.

What are your favorite space-related movies?

2001 Space Odyssey, because it's so prescient. You watch that movie and it was pretty bang-on in terms of the way things were going to go. When you watch it now it still doesn't date. They fly to the moon on a Pan-Am shuttle and there's a Hilton in space. That's sort of on the edge of what's happening now in various forms. Between Elon Musk and Bigelow [Aerospace], it's on the edge of realization. I just think as a bit of space opera it's wonderful. It's a big canvas film.

I really did enjoy Solaris to be honest with you. I know I'm supposed to say the Russian version is better. But I thought it was quite thoughtful. I also went to the London premier of Gravity and enjoyed that. Sandra Bullock was there although she was in the middle of everyone and I was in row 548. I enjoyed Gravity principally because I think that's the first space film that is not a science fiction film. It's a drama with an industrial setting but that industrial setting happens to be space. That's quite an interesting thing, because they hadn't invented any particular crazy alien thing there or killer bugs in space. In that regard it's not a science fiction film any more than Das Boot or The Perfect Storm is a science fiction film. The special effects were dazzling, but I thought it says something about this time, that they'd write that sort of drama, that sort of content.

How does it feel to be the 380th person interviewed for Zulkey.com?

It feels fantastic actually! I'm very pleased that you liked the book enough to look me up. It's a great and surprisingly clear line given the number of proxies you go through to get to my mobile phone. Modern technology never ceases to amaze me.