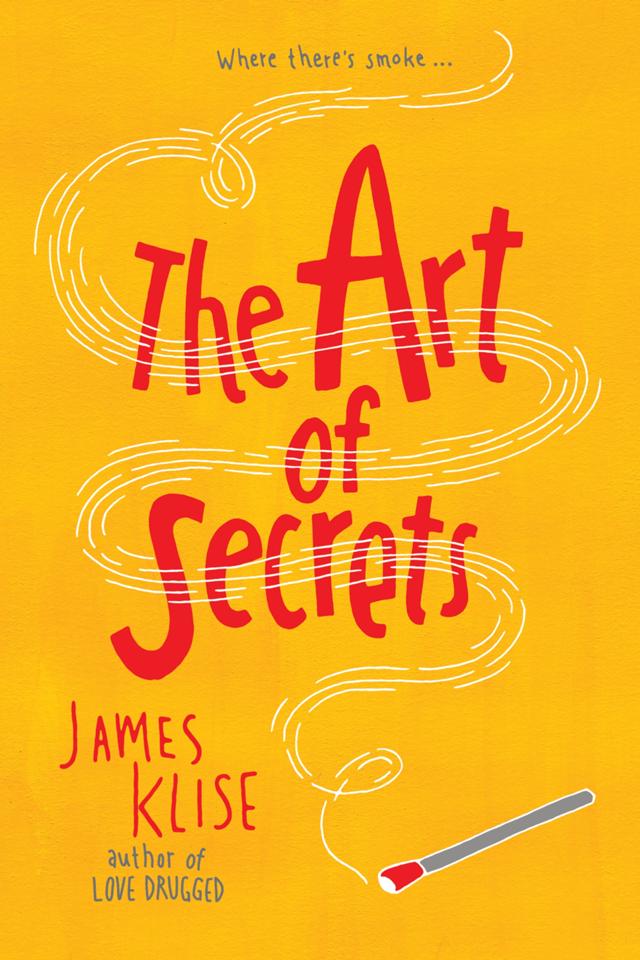

Today's interviewee is a friend of mine who is the author of the sweetly funny and heartbreaking Love Drugged, a YA book about a high school boy who tries to "cure" his gayness through dangerous non-FDA-approved drugs. More recently he published The Art of Secrets, a mystery about a young girl whose house is burned to the ground (possibly because of a hate crime), and the way her community rallies around her and then retracts the support when it's revealed that the family has come into possession of a priceless work of art. When he's not writing, he runs a high school library here in Chicago, and sometimes hangs out with writers like me who adore him for his supportiveness, honesty, and humor. You can learn more about him here.

Today's interviewee is a friend of mine who is the author of the sweetly funny and heartbreaking Love Drugged, a YA book about a high school boy who tries to "cure" his gayness through dangerous non-FDA-approved drugs. More recently he published The Art of Secrets, a mystery about a young girl whose house is burned to the ground (possibly because of a hate crime), and the way her community rallies around her and then retracts the support when it's revealed that the family has come into possession of a priceless work of art. When he's not writing, he runs a high school library here in Chicago, and sometimes hangs out with writers like me who adore him for his supportiveness, honesty, and humor. You can learn more about him here.

You've been writing for a long time: when and how did you come to the YA genre?

That's correct, for fifteen years I only wrote and published short stories. I don't know why I was so devoted to short stories. They caused me nothing but heartache! But then I began working at a high school, spending my days with teenagers, and reading some of the great things coming out for them (including the wonderful An Off Year, by the way). I was well into the first draft of Love Drugged, when it occurred to me that this would be something for younger readers.

How was The Art of Secrets different from Love Drugged for you, process wise?

Very different. When I wrote Love Drugged, I didn't use an outline. I had a specific character and what felt like a compelling situation and just dove in like a fool. But The Art of Secrets is a mystery, and those require more initial plotting, so I began with a loose roadmap. I didn't stick with the initial map, but it helped a lot. I'll never work without a map again. Do you outline? I always thought they'd be the kiss of death, until I started using them.

I do not outline as much as I should. An outline was provided for me for my most current project and it made life so much easier, but then again, having one given to you is a lot nicer than writing one yourself. How did the two books differ in terms of how they make you feel? If the first one made you think, "Yes, finally, I published a book," what comes next?

My feeling is that most of the personal pleasure occurs before a book comes out. When you're working on a book, it feels almost alive, because there's so much possibility, so much potential. But then it's published and it exists in a different, more real yet more limited way. There's the accomplishment and the sheer good luck of publication, of course, but also a little bit of sadness that my part of the process is over. I felt that way with both books. As soon as each book came out, I wanted to go back to the fantasy and the possibility, and I started another book. That's where I am now.

What are some examples of ways your students have influenced your writing?

My library patrons remind me that readers are impatient. No one wants to be bored. Teenagers absolutely will return a book if it doesn't catch their attention by page two, or if it loses their attention after page 50. Also, as a writer, I take real comfort in seeing their wildly diverse reactions to books. It's reassuring to remember that not every book is for every reader. In fact, the better the book, the more extreme the reactions. The students also remind me that book covers matter, almost more than anything. I'm starting to think that book cover designers should get a bigger cut of the profits, their influence is so powerful.

What are the kids into these days, when it comes to books?

The kids at my school (on the North Side of Chicago) ask for books about gangs (that's #1), zombies, serial killers, sex. In other words, all the things that scare them. No teenager ever asks me for funny, but they like humor when they find it in a book. There's also the eternal fascination with A Child Called "It" and its sequels. Do you know this book? It's a memoir about surviving child abuse. It's insanely popular, and it astounds me that it hasn't spawned an industry of violent, graphic child-abuse narratives.

I am not familiar with that book but now I am morbidly curious, naturally. You are the youngest of six kids and by all accounts your family is a happy one. What advice do you have for new parents on raising siblings who are also pals?

I'm not a parent, as you know, and yet I do have very strong opinions about subjects I know nothing about, so thank you for asking. My feeling is that it is not the job of parents to make sure their kids are friends. It's the job of the kids to make sure they're friends. Right? When did today's parents start believing they have so much control, or wanting such responsibility? Likewise, I'd say that it's not a parent's job to make children interesting or creative or compassionate or hard working or whatever. If I have any good traits, it's because my parents demonstrated them first, and I wanted to be like them. What I'm trying to say, Claire, is that no matter what you do, your kids are going to be completely fine and fantastic, just like you.

Blush. Is there a particular reason (beyond it being what you know) why you set both books in Chicago? How did the city affect each story?

I suppose Love Drugged could have been set in any city, but The Art of Secrets is closely connected with Chicago, because of the Henry Darger element. The story hinges on the unexpected appearance of Darger's artwork in a school auction. I think young people like seeing their world on the page. It's fun to include real street names and landmarks. One of the reasons I loved the novel The Time Traveler's Wife was that I could picture so many of the locations, because I know them. I will see any movie that has been filmed in Chicago--even movies I don't expect I'll enjoy--just to see how the city has been represented to the world.

The Art of Secrets is told in a collage-type of format. How early in the writing process did you know you wanted to use that structure? What were the benefits and drawbacks of writing in that structure?

The Art of Secrets is told in a collage-type of format. How early in the writing process did you know you wanted to use that structure? What were the benefits and drawbacks of writing in that structure?

The structure came first, before I began writing anything. I knew I wanted to tell the book from the point of view of a chorus. I wanted to play around with voices in a series of monologues. Before I began, I knew what the crime was, how the crime would unfold, and who was responsible for the crime. The fun part (for me) was seeing how each character would personally respond to each new development. There weren't any drawbacks, really, except that it was challenging to keep the voices distinct. But even that was part of the pleasure. Those voices appeal to my theatrical side.

What advice, both as a YA author and as a librarian, do you have for other YA authors on how to make themselves and their work appealing to other school librarians?

This is a tough one! The obvious answer is to write something that will make lots of teenagers turn pages and ask for more. I will add that I am drawn to any book that generates a reaction that isn't only about the book. If that makes sense? For example, sometimes I'll let the kids choose a selection for book club, and it will be a fun read, but then it turns out there's nothing for us to talk about. That's frustrating. I'm always on the lookout for edgy books that have some real-world, personal relevance, or spark debate. A better debate than: Peeta or Gale? Edward or Jacob? Those conversations always leave me watching the clock, eager to end the club meeting.

What has the reaction or dynamic been so far when one of your students reads your work? Do you sense that they see you differently?

Seeing my name on a book humanizes me in their eyes, I think. It reminds them that I have a life away from the library. The first book was about a closeted, freaked out teenager, and they know I'm a gay now, so maybe they think the character I wrote about in the first book was me. Some of them want to be novelists, and they have questions about how to get published. But it's so hard to write a novel, especially for a teenager. A novel takes a lot of time to write, and if a young author is growing and changing over time, it's hard to keep interested in a project and you end up with a bunch of abandoned manuscripts. So I mostly encourage smaller projects. Something that can be written over a weekend and then shared at a club meeting, with cookies.

The two I keep in mind are Tim Robbins in The Shawshank Redemption, prison librarian, nobly serving elderly patrons (and always writing letters for better funding), and the crazy bow-tied dude in Sophie's Choice, who is so cold and intimidating when Sophie comes in looking for "19th century American poet Emile Dickins" that he causes her to pass out.

How does it feel to be the 383rd person interviewed for Zulkey.com?

Precisely like I'm standing before your desk, asking for information about "19th century American poet Emile Dickins."

Â